Study says AI narrows research focus

A new study from Tsinghua University has identified a paradox in AI-assisted scientific research: while artificial intelligence boosts individual scientists' productivity, it also leads to a collective narrowing of research focus across the scientific community.

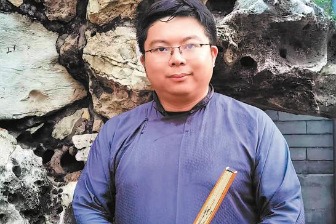

The research, led by Li Yong, a professor in Tsinghua University's department of electronic engineering, was recently published in Nature and reported by Science.

The team launched the study to address a puzzling contrast: the rapid rise of high-profile AI-powered breakthroughs alongside a documented decline in disruptive scientific discoveries across disciplines.

"We observed an intuitive contradiction between micro-level efficiency gains and macro-level feelings of convergence," Li said in an interview with China Daily.

To move beyond anecdotal evidence, the researchers constructed a large-scale panoramic knowledge map, analyzing 41.3 million academic papers published over a period of nearly 50 years.

They utilized a novel approach combining expert annotation with large language model reasoning to identify AI-infused research, achieving an identification accuracy of 0.875, with 1 representing a perfect score.

The findings showed that at an individual level, scientists who use AI publish 3.02 times more papers, receive 4.84 times more citations, and become project leaders 1.37 years earlier than peers who do not use the technology.

However, this "individual acceleration" comes at a collective cost. Research incorporating AI shows a 4.63 percent decline in knowledge breadth and a 22 percent drop in cross-disciplinary collaboration. Citation patterns in AI-driven studies form a "star-shaped structure", heavily concentrated around a small number of foundational AI papers, pointing to a trend toward homogenization.

Li explained the phenomenon using the metaphor of "collective mountain-climbing".

"Most researchers, influenced by tools and trends, converge on a few popular, data-rich 'known peaks' while largely ignoring the 'unknown peaks'," he said.

Current AI models, which rely heavily on vast datasets, act as powerful "climbing accelerators" on established research paths. This creates a form of "scientific gravity" that steers the research community toward areas where AI performs best, systematically marginalizing data-scarce but potentially transformative frontiers, Li said.

The study identifies the root problem as a fundamental "lack of generality" in existing AI-for-science models — a systemic issue involving data availability, algorithms and entrenched research incentives.

AI's strengths in learning and prediction are most pronounced in data-rich fields, while its effectiveness drops sharply in frontier areas where data is limited or nonexistent, Li said.

The strong personal incentive to use AI for rapid publication further amplifies the trend, prioritizing problems that AI can solve over those that are more original or scientifically critical, Li added.

In response, the team has developed OmniScientist, an AI system designed as a collaborative "AI scientist". Its core philosophy is to evolve AI from a stand-alone efficiency tool into an integrated participant in the human scientific ecosystem.

The system can autonomously navigate knowledge networks, propose novel hypotheses and design experiments, particularly in cross-disciplinary and data-sparse fields, Li said, emphasizing its potential to expand scientific exploration rather than merely accelerate existing research trajectories.

For practicing scientists, Li recommends a mindset of "conscious, active steering of AI". Researchers should allow fundamental scientific questions — rather than AI's current capabilities — to guide their work, deliberately allocate resources to explore areas where AI performs poorly, and use AI to strengthen, not weaken, interdisciplinary collaboration.

Li also said educational institutions should teach critical thinking about AI's limitations alongside technical training. Journals and academic institutions should reform evaluation systems to better reward research diversity, originality and long-term exploratory projects.

For frontier research, Li said longer evaluation periods and greater tolerance of failure are needed to provide institutional support for scientists willing to explore the "unknown mountains".