Iconic hall reopens after decade-long renovation

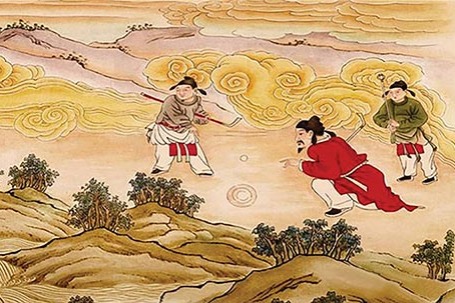

It was Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) emperors' "home office" in the Forbidden City in Beijing, the former royal palace of China.

First built in 1537, Yangxin Dian, or the Hall of Mental Cultivation, became a spotlight of imperial politics and many historical anecdotes after the workaholic Qing emperor Yongzheng moved there to handle national affairs during his reign (1722-35).

His son, the fine art enthusiast Emperor Qianlong, set up an exquisite study in the west chamber of the hall to cherish his beloved, rarely-seen paintings.

Decades later, Empress Dowager Cixi sat behind a silk curtain in the east chamber to listen to the assembly and hold the real power and destiny of a country in crisis in her hands.

Even after the Qing Dynasty fell, the last emperor Puyi was allowed to live in the inner court of the Forbidden City, where Yangxin Dian is located.

After being closed for a decade for comprehensive studies and another round of renovation, this hall full of stories, also a key attraction in the Forbidden City — officially known as the Palace Museum today — finally reopened for public visits on Friday.

Cold weather in Beijing cannot quench crowds of history fans' enthusiasm. Perhaps, it is the last big gift provided by the museum on the centennial anniversary of its founding, which falls this year.

Historical settings of Yangxin Dian from different periods have been resumed for various rooms: Visitors can see the east chamber from the Cixi era and the west chamber from Yongzheng and Qianlong's time, according to Wen Ming, deputy director of the court history department of the Palace Museum. The main hall in the middle maintains the original setting when the emperors held assemblies.

"I've waited for this moment for a long time," said visitor Yuan Yizhou, a college student from Fuzhou, Fujian province. "Seeing the scenes is like time travel."

She wore a coat in the style of a Qing imperial robe to create a reminiscence of old days, but said it was a pity that due to the narrow space of the hall, it cannot receive tourists. No visitors are allowed in the indoor area.

Still, seeing it through the window is already a visual feast. Over 1,000 cultural relics are now displayed in Yangxin Dian. Of course, some fragile ones, like silk pieces and paintings, have been replaced by replicas.

Zhao Peng, a heritage architecture expert, explained that the relics of Yangxin Dian faced a grim situation due to their age by 2015. The regular opening then left many safety issues unresolved. It was thus closed for renovation due to its "health".

Over 4,300 spots across the architecture were fixed in the past decade. Experts also restored 500 paintings and settings, 120 groups of architectural decorations, and 88 plaques and hanging couplets.

"The biggest plaque in the main hall weighs more than 200 kg," said Wang Hui, head of the architectural conservation management department of the museum. "After we fixed its wooden carvings, it took five workers to put it back."

All the relics of Yangxin Dian were digitized to create an archive for this monumental building of the Forbidden City. Many hidden historical details have come to light thanks to the preservation.

For example, in pillars under the main hall's projecting eaves, renovators discovered that the metal pipes inside the pillars were made of a tin-lead alloy, a waterproof material perfect for drainage. The transparent canopy used for lighting on the north wall of the east chamber was found to be made from seashells.

Separately, two playbills of traditional opera performed on the eve of the Chinese New Year were also found in a brick carving vent. Some Qing royal who was enjoying leisure time may have randomly left them there. Accidentally, they became a time capsule recording a long forgotten celebration beyond the history books.

"They provide valuable materials for the study of court entertainment culture," Wang said.

wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn